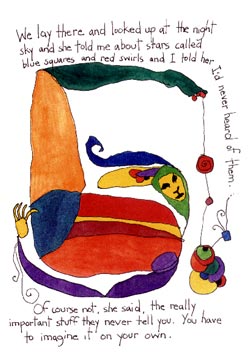

When our first child, Fiona, was born, our friends Trisha and Abel gave her this beautiful print, set in a frame they’d made themselves:

This print was our introduction to the charming work of California artist and storyteller Brian Andreas. In case you can’t read the text around the image, here’s what it says:

We lay there and looked up at the night sky and she told me about stars called blue squares and red swirls and I told her I’d never heard of them. Of course not, she said, the really important stuff they never tell you. You have to imagine it on your own.

The Andreas print hung in the nurseries of the two houses we occupied during our time in California. When we moved to Vermont, decorating being what it is, the print ended up in the girls’ bathroom. (BUT, Trisha and Abel, if you’re reading this, it’s in an extremely important place in the bathroom: facing the toilet. So, once all three of our girls are potty trained, they’ll have to stare at this print every time they . . . Okay, I’m not sure this is making you feel any better, so I’ll stop now!)

Anyway, the other night I was in the bathroom with all three of our girls, helping them perform their bedtime ablutions, when one of them zeroed in on the print on the wall, the print they’ve lived with every day of their lives, as if seeing it for the first time.

“Read it, Mommy.”

So I read the text, and their eyes lit up. “Read it again!” “Again!” I must’ve read it five times over. They were caught up in the magic of the words.

Then they wanted to know about the image. “Who’s that lady? Is that the lady in the story?” “What’s she doing? Is she doing a somersault? A headstand?” It was Fiona who asked, “What’s that stuff hanging off her foot?”

“I’m not sure, Fiona,” I answered, “but I think maybe it’s the blue squares and red swirls.”

“That’s funny,” she said, “How can somebody have stars hanging on their foot?”

“Well, it’s art, Fiona, and art doesn’t always have to make sense.”

Pause. “Mommy, what does that mean, ‘make sense’?”

That’s how I found myself stumbling over what it means when something either does or doesn’t “make sense.” And in trying to explain “sense” to a four-year-old (“Well, things are usually a certain way, so if something doesn’t make sense that means that it isn’t the way things usually are . . .”), I had a fascinating glimpse into my child’s mind. Because, it turns out, Fiona has lived for four years without the concept that some things “don’t make sense.”

I’m hesitant to generalize from Fiona to all children, but I suppose this might be what we refer to when we talk about the “innocence” of childhood; not that children are angelic and do no wrong (HA!), but rather that they live in a world where anything could be possible. It takes experience to know that there are certain rules regarding how the world should be, and to perceive when something breaks those rules. Experience, of course, is exactly what all children lack.

I’m guessing this is why children ask so many questions; they honestly expect that

every question has an answer, that everything will “make sense” if you just ask the right question. Fiona, at four, is starting to become more savvy and world-wise — she did, after all, question how somebody could have stars hanging from their foot. But if I’d responded authoritatively that it was possible to hang stars from your feet, she probably would have bought it.

I can’t remember what it’s like to live free from knowing that some things don’t make sense; to expect that every question has a logical answer. It’s begun to dawn on me that very soon I will be what could be described as “middle aged” — that I will have lived half of my expected life (assuming the best). And if there’s one thing I’ve learned from living half my life, it’s that every question does NOT have an answer. There are some things, mostly things pertaining to love and death and justice, that I’ve had to accept I will go to my grave not understanding.

Like the cold-blooded killing of twelve innocent people in an Aurora, Colorado movie theater.

In the weeks following the Aurora shootings, many beautiful reflections and thoughtful analyses have been written. It’s not my intent to add to that volume; others more qualified and eloquent than myself have already spoken. But all these reflections and analyses are in agreement on one fact: that the murders in Aurora do not make sense. Regardless of your views on mental illness or violent movies or gun control, this is not the way the world should be.

Here’s something else that doesn’t make sense to me:

The Sunday after the Aurora shootings, an 80-something-year-old man who has been a member of our church for decades stood up following the service to speak a few words about a difficult decision our church is making. This man has fought in two wars, he and his wife struggle with the health issues that go along with being 80-something, and he’s seen many close friends die in the past year alone. I can’t imagine what else he must have seen in eight decades; I’m worn down enough by what I’ve seen in three.

For his advice to our congregation, he quoted from Deuteronomy, the words that Moses repeats when he’s at the end of his life and sending the Israelites on to the promised land he’ll never enter: “Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged.”

HOW can someone who’s experienced the horrors of two wars, countless deaths of loved ones, and all that’s gone wrong in this world over the past century stand up and still have enough faith in God to say, “Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged”? HOW has he not sunk into bitterness and hopelessness? It doesn’t make sense.

But that’s the kind of world we live in: a world where things don’t make sense in horrible ways, where people watching a movie are shot dead for no reason at all — and a world where things don’t make sense in beautiful ways, where our elders can still somehow counsel us to be brave and have faith. A world where these things can happen so close together, like the inhale and exhale of a single breath.

It’s exciting that, for my kids right now, anything is possible and everything has an answer. But when I think about it, I wouldn’t want to return to a state of innocence that expects everything to make sense. There’s a certain freedom in recognizing that some questions have no good answers. And when my children find those spaces, those spaces that hold grief or mystery or hope instead of an answer, that’s where their hearts and minds will be free to sing.

Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged.

The really important stuff they never tell you. You have to imagine it on your own.

Pingback: Sense « THE PICKLE PATCH

Faith – I continue to be touched by your writing. You are so gifted at sharing your life and making the world larger for me. This is a lovely piece with a wonderful ethereal introduction to a new artist and your family.

Thanks again.

Thank you for making so much sense in this post. I recently found myself editing something I had written and realize that I used the word “sense” in one sentence 3 times (oops) and in 2 senses! I think there is more going on here than we realize—like blue squares and red swirls. Thanks again.