Walking into Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles on a Friday morning is an experience that I truly struggle to find an accurate analogy for. I know because I tried – and failed. Tons of eager faces packed tightly into the small, yet bright and inviting building that stands in contrast to the surrounding area (Skid Row is just a few blocks away). Women carried children, groups came in to claim the small collection of seats, waiting to hear if their name would be called for the job lottery that week. There is little sense of privacy or escape as nearly all staff offices transparently declare their occupants to the hustle outside. I struggled to find a spot to stand as everyone, most bearing inked testimonies of their pasts, gathered around for the morning meeting led by Father Greg Boyle. Despite warnings that it would be, the whole experience felt slightly overwhelming.

It takes a certain kind of person to thrive in the chaos of this environment.

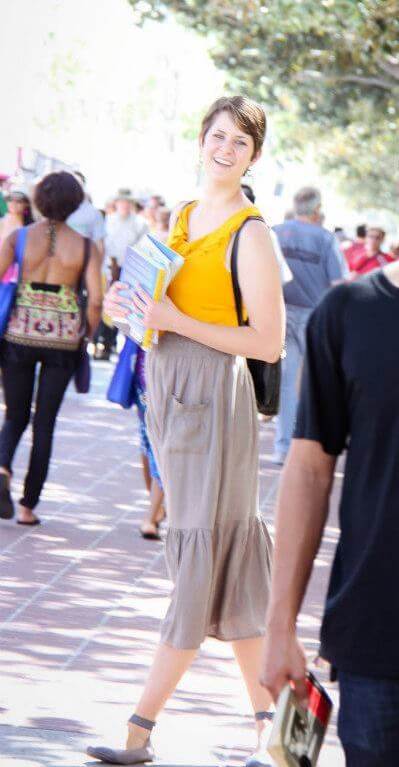

A person like Lauren Grubaugh.

Homeboy Industries is an organization that seeks to reach out to former gang members and the formerly incarcerated community of the at-risk LA area. “Homies,” the people the organization is geared toward helping, are given opportunities for employment at Homeboy itself as well as job training, tattoo removal services and various other types of real-world preparation classes. To the casual and curious visitor, there is no sense of pretense here. Upper level staff members mingle freely with homies coming and going. Tour groups are not catered to and shown the neat and well-put together side of the operation. Rather, they are whisked into the pulse of the organism-like body that Homeboy is.

And it was into this strange fusion of chaos and love and warmth that my friend Lauren stepped into months before she brought me there. And it was here, amongst a culture entirely different from that of her own small hometown, that she found a home.

Lauren is a tall, white, young woman with a fresh degree from UCLA and a full ride scholarship to Fuller Theological Seminary for the upcoming fall. So aside from the fact that she is a fluent Spanish speaker, she hardly fits the description of the average person who walks through the door of Homeboy.

But Lauren is known and loved there. And it is easy to see why. Walking through the small yet packed facility, there is hardly a person that Lauren doesn’t say hello to. And if they are not acquainted, she is quick to introduce herself.

No one escapes her notice — the “homie” directing traffic at the parking lot around the corner, or the waitress at a local hole-in-the wall Mexican restaurant. Her friendliness and love for people is not limited to her work with Homeboy. Her tiny, one-room, appliance-devoid granny flat is filled with reminders to send people cards. Her inquisitive mind probes not only the depths of academia, but the more important caverns of human hearts.

Ever heard the phrase, “Youth is wasted on the young?” I will be daring enough to say that this is not a phrase Lauren will use when physical age catches up with her already old soul. Hers is one that seeks adventure and independence, but also one that has found such deep meaning and strength in a life lived with people.

“Conspire” is what she called it. It is a word associated with hooligans and their shenanigans. But it also means to “breathe together.” And at Homeboy, Lauren has found the opportunity and the group of people to do this with in a way quite opposite from what we would normally associate with such a provocative word. She is “a part of a community” she says, “that conspires to do good and inspires people to be their true selves.”

Despite the chaos, it was refreshing to spend a day at Homeboy — to be greeted with warm hello’s and handshakes was no strange thing. To be welcomed with sincerity from everyone, from the homie cleaning the facility to one of the brains behind the whole operation, was a welcome surprise.

And this is why Lauren does well there. Because in her life, career and independence and the haughty self-advancement that often describes the driven women of this day are submitted to an understanding that people are better than success, that being in community with the marginalized is, as Lauren puts it, “life-giving.”

We left Homeboy that day a couple hours later than the normal closing time as Lauren was preparing for one of the organization’s biggest fundraisers the next evening. But we were stopped in the parking lot by a woman. My introverted mind and tired body was ready to peace out, but Lauren lent a sympathetic ear to the distresses of this woman. Because, you see, clocking out and exiting the building does not mean the end of the kind of work she does with Homeboy. It is an invitation to offer love to people in a way that isn’t required of her, when no one is watching, when she doesn’t receive anything in return.