I am a bleeding heart idealist. I believe in the power of love, justice, and compassion. I believe that we are ALL supposed to roll up our sleeves and try to save the world, to tackle the BIG PROBLEMS like poverty, injustice, disease, violence, and environmental destruction. I believe that, even if we won’t ever be able to turn the world into a completely peaceful kingdom by our own efforts, to have anything less as our goal is to pull the shades and wait for the end. I believe that God put us here to try to love each other (even though we’d mess it up). And I KNOW that nothing threatens this idealism more than living with a development

economist.

I’m talking about my husband.

Erick entered his field based on a certain amount of idealism, too. In fact, the deciding factor behind his pursuit of a PhD in economics was the time we spent helping coordinate a school and house build in Tanzania. Largely because of that experience, he focused his research on how economic factors affect the spread of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa.

But spend enough time working hard in any field, and a certain amount of cynicism seems inevitable. Lately, Erick has become cynical about everything from NGOs, to short-term missions trips, to “humanitarian tourism,” to even . . . Bono. When well-meaning, idealistic outsiders try to “help” in difficult and complex situations, he tells me it’s often no help at all and sometimes even makes things worse. For instance, a team of westerners who go to a third world country in order to build houses or schools is often taking over jobs that locals can — and should — be doing; I believe the official economic term is “unintended consequences.” Now he comes home after a full day of researching how to make the world better, and tells me that no interventions really effect meaningful change — unless maybe you pay people enormous amounts of money as a reward for feeding their own children. So Erick and I have a lot of discussions around this topic, often beginning when I say, “Guess what amazing things so-and-so or such-and-such is doing!” and he puts on his professor face and goes, “Hmmmm . . .”

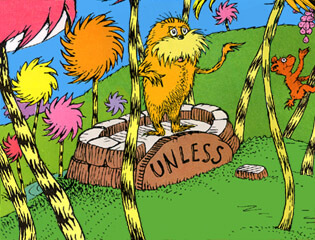

The title of this post is taken from Dr. Seuss’s book The Lorax. For those who aren’t familiar with the story, the Lorax is a creature who “speaks for the trees” that are being cut down by the greedy Once-ler. After the last tree is chopped down, the Lorax flies away, leaving behind a pile of stones with the word “UNLESS” engraved upon them. The Once-ler, trapped in the barren wasteland he’s created, stews over the meaning of UNLESS, until finally he gets it:

UNLESS someone like you

cares a whole awful lot,

nothing is going to get better.

It’s not.

I’ve stewed, too, over whether that catchy little rhyme is true. And I’ve decided that I think it is true. A development economist might disagree that one person’s caring can make anything measurably, objectively better. But I’m still an idealist.

And yes, I am disagreeing with my own husband. I’m disagreeing with gratitude, though — gratitude that I have a husband who engages with me around hard topics and forces me to defend my idealism. (And despite the cynicism, we’re still talking about a pretty tenderhearted guy, who successfully navigates a house filled with four noisy and dramatic females.)

Here’s why I think that NGOs, short-term missions trips, humanitarian tourism — and Bono — are important:

UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, there will be needs and injustices in the world that are ignored. Of course, there will always be needs and injustices that go unaddressed, and your ability as one person to make a significant dent in these issues is miniscule. But by making a choice to care, you are still sending an important message that you’re not going to ignore the things that are wrong with our world. You’re sending that message to the people you’re choosing to serve, to the people who know you, and even to the marketplace. That just might have a powerful ripple effect across time. You’re not as powerful as you think you are, but you’re not as powerless as you think you are, either.

It’s like taking a meal to someone who’s grieving. That action may seem pretty insignificant; one meal can’t take away their loss, or heal their pain. It could even be a silly gesture: maybe they’re too sad to even eat, or yours is the twentieth lasagne they’ve received in a week. So, should you even bother to take them a meal? Of course you should! More important than the food itself is the gesture of caring, and the message that sends to your grieving friend that their heartache isn’t being ignored.

UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, we’ll never figure out the best ways to solve these problems. The history of humanitarian aid is riddled with stories of unintended consequences: well-meaning outsiders who took jobs from locals, built things that were ultimately useless or couldn’t be maintained, and imposed their own ideas without fully understanding the needs of those they were “helping.” So, is it best to just bow out, to let the marketplace and the local population hash out the solutions to their own problems?

I don’t think so. Deep needs or injustices usually arise from complex imbalances that render the marketplace or the local population unable to address these issues quickly or thoroughly; they don’t have the social or economic power. In these cases, it can be extremely effective when people who DO have more social or economic power lend a helping hand. Not that the local population couldn’t resolve things eventually, not that they need rescuing like frail damsels in distress; it’s more like giving the problem solving process a shot of adrenalin, in the form of additional brains, muscles, and money.

And here’s the really, really important thing: I think it’s just as patronizing to imply that those we try to help are somehow powerless against our misguided good intentions, as it is to imply that they need rescuing in the first place. In my experience, the most effective and long lasting programs aimed at addressing BIG PROBLEMS are the ones that are the most collaborative. They’re the programs that invite everyone to the table — the helpers AND the help-ees — and create a climate of respectful listening and discussion. They’re also the programs that place a great deal of the power and responsibility directly into the hands of those being helped.

We don’t have a shot at ever solving the world’s biggest problems unless we TRY. And trying will naturally involve some misfires, but that’s no different than the rest of life: even with the very best intentions, people are still people, the world is still the world. But just because some programs are misguided, and just because the big problems are a tangled mess, doesn’t mean that we should abandon any attempt to help; you throw out the bad, and keep working together to do better.

UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, you’ll probably never care a little. One critique of things like short-term missions trips, humanitarian tourism, and writing checks to popular NGOs is that these activities are fairly glamorous, relatively easy to do, and short-lived. You can drop in to a third world country or an inner city for a week or so, do your helping, and then leave feeling great about yourself and looking noble to everyone else.

I say: you have to start somewhere.

Every once in a while, these experiences change people so much that they can’t go back to their old lives; they pull up their stakes and move to that third world country or inner city with a long-term commitment to live, learn, and help. Or they change jobs. Or they go on more trips. I know that the world would be short one development economist (and what a tragedy that would be!) if not for a two-week trip to Tanzania in 2005.

But more often, these experiences change us little by little, priming our hearts for what just might be a lifetime of steady, non-dramatic caring.

I have come to believe that the most important thing is caring for people in my own small town. In fact, the reason we need most of the nonprofits out there is because we don’t tend to take good care of each other. You know all those stories about how you can make the biggest difference in your own backyard, and the janitor who touched lives just by doing his job excellently, etc? Well, it’s TRUE; I can assure you as someone who spent half a decade working for nonprofits, and even my development economist agrees with me on this point. Just as one drop of food coloring has much more impact if you add it to a teaspoon of water instead of a gallon, you can most effectively make the world better simply by helping the people directly around you.

If this sounds like an easy cop-out, a wimpy vision, I assure you it’s not; it’s usually harder to help the people right around you than to support organized global relief efforts. It takes more time and intimacy — two things that are scarce and/or scary for most of us. But what does it say about my ideals if I’m sending money to international nonprofits, or going off on humanitarian vacations, but ignoring the needs of my neighbors? (And yes, I know we’re all neighbors, but I’m talking about my actual neighbors.)

The funny thing is, I think sometimes we’re better able to carry out these small, local acts of service if we’ve first taken that big, glamorous humanitarian trip. We may not uproot our lives to become career humanitarians, but we may have our eyes opened to the daily needs all around us, to the power of love and caring, and to the feeling that when we help just a little, we’re somehow getting closer to who we’re meant to be.

Here’s a little story for you, in closing:

My husband has a former student who arrived in Vermont from his native Kenya following a journey of amazing determination. Shortly before graduating from Middlebury College this spring, he founded an NGO called the Ungana Scholars Project, which provides scholarships for Kenyan students to attend secondary school and college.

He says that it was my cynical husband’s “Seminar in Economic Development” that helped inspire him to found this NGO.

So I guess you can be cynical and idealistic at the same time: a cynical idealist. That’s probably not a bad thing to be.

What do YOU think?