I recently read Virginia Lee Burton’s classic children’s book Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel to my daughters. For those whose lives aren’t steeped in children’s literature, it’s the story of Mike Mulligan and — you guessed it — his steam shovel, named Mary Anne. And here’s the thing about Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne:

I recently read Virginia Lee Burton’s classic children’s book Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel to my daughters. For those whose lives aren’t steeped in children’s literature, it’s the story of Mike Mulligan and — you guessed it — his steam shovel, named Mary Anne. And here’s the thing about Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne:

When people used to stop

and watch them,

Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne

used to dig a little faster

and a little better.

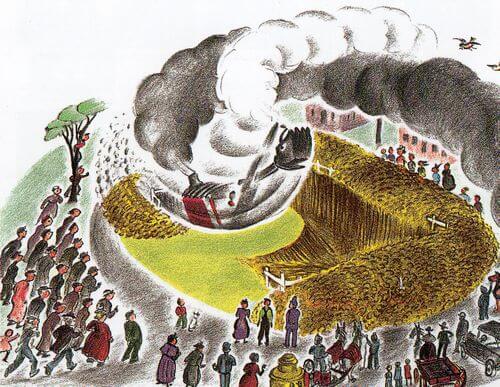

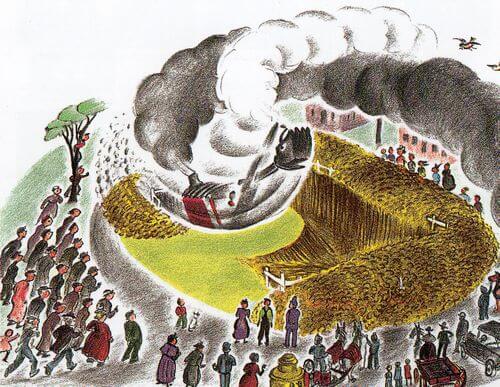

The fact that Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne dig faster and better when they’re being watched is a central plot point; when they have to dig the basement of Popperville’s new town hall in just one day, it’s their growing audience that spurs them on to complete the job that “would take at least a hundred men at least a week to dig.”

On the one hand, this is a nice message about community support and involvement. The town council shows up, and the fire department, and the local elementary school, and then the switchboard operator calls the next town over, and the WHOLE TOWN turns out to watch Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne dig.

On the other hand, that Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne were so influenced by spectators made me a little…uncomfortable. What message is this book sending my children? I wondered. That your performance should depend on how many people are noticing? Whatever happened to being self-motivated? To doing your best regardless of whether anybody sees? To “Dance as if nobody’s watching?”

It bothered me, because it’s completely opposed to the advice I’ve been given about writing.

I’ve been writing a personal blog for about a year now, about life and motherhood — mostly my life and motherhood in Vermont. For anybody who might think that I just dash off these blog posts in one sitting and hit “Publish,” I’m very flattered, but nothing could be further from the truth. I love writing, and because I love writing, I want to honor it by writing well. With a few exceptions, I typically have written whatever post you’re reading at least one month prior to when it shows up on the blog. I write it in pieces, whenever I have a quiet block of time, and then I revisit it obsessively to edit.

Because this process is something I enjoy and want to get better at, I also occasionally read books about writing. A couple of the best — and I’m not unique in thinking this — have been Anne Lamott’s Bird By Bird and Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. And Anne Lamott and Stephen King and their compatriots all say the same thing:

Don’t worry about whether your work ever gets published. Publishing won’t solve all your problems, and may even create MORE problems for you. Write for YOU, because you love to write and need to write.

That seems like such good advice. If I’m constantly looking over my shoulder when I write, trying to please some imaginary audience or turn out material that’s “publishable,” my writing probably won’t be very honest or genuine or enjoyable. Even Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne didn’t sit around waiting for an audience before they started digging; they got started, and then the audience came.

But still… When people used to stop and watch them, Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne used to dig a little faster and a little better.

Here’s where Anne Lamott and Stephen King’s advice breaks down: Writing is an act of communication. Most people write because they feel like they have something to say. And if you have something to say, talking to yourself starts to feel kind of sad and weird after a while. The fact is that the best way to communicate to the most number of people is to get your writing published.

This isn’t just about writing, of course. This is about the tension between doing whatEVER you love for its own sake, versus wanting external validation for that thing.

It’s no different with anything that people work hard to become good at. If you love baking, you usually don’t sit around eating all those pastries by yourself. If you make art or do research or know how to help people fix things (or themselves), there comes a point at which it would be unnatural not to share those things with the broader public. Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne loved to dig and were good at it, but they didn’t just dig holes in their own backyard — they dug for other people AND (gasp!) FOR MONEY.

Another way of saying this: Our gifts are meant to be shared. Sharing the things we love doing and are good at is how we each make an imprint on the world, no matter how small. If you’re spiritually inclined, sharing your gifts is one way you worship.

The hard truth of this: There are a lot of very gifted people out there, and relatively narrow opportunities for gift-sharing. You could spend all of your time trying to share your gift (trying to get published, get a gallery show, open your business, etc.) at the expense of actually doing what you love. And that’s just as silly as keeping your gift all to yourself.

I don’t have much relief to offer when it comes to this tension between doing what we love and wanting to share those things with the public. But that’s okay; not all tension is bad, or needs to be relieved. Also (I never thought I’d say this), in many ways this is the genius of the internet: I can easily publish my writing online, and some people will read it — even if it’s just my friends and family — and offer comments and feedback. I write because I love it, and because I need to write to rid my head of the pressure of unexpressed thoughts, but it’s those comments and feedback that keep me going, that tell me I’m not just shouting into a void.

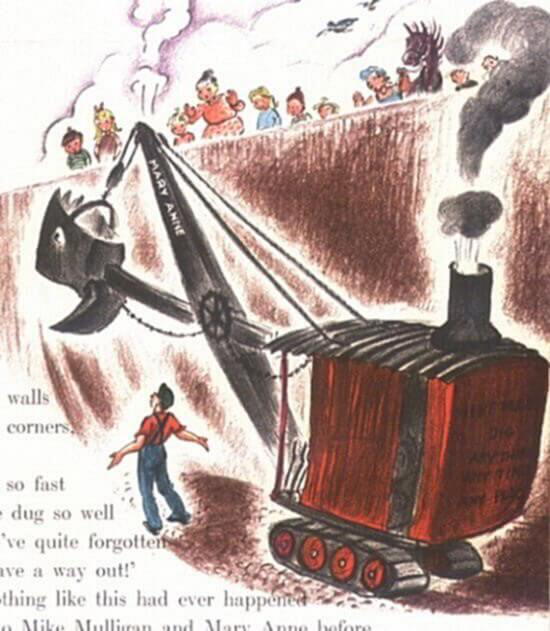

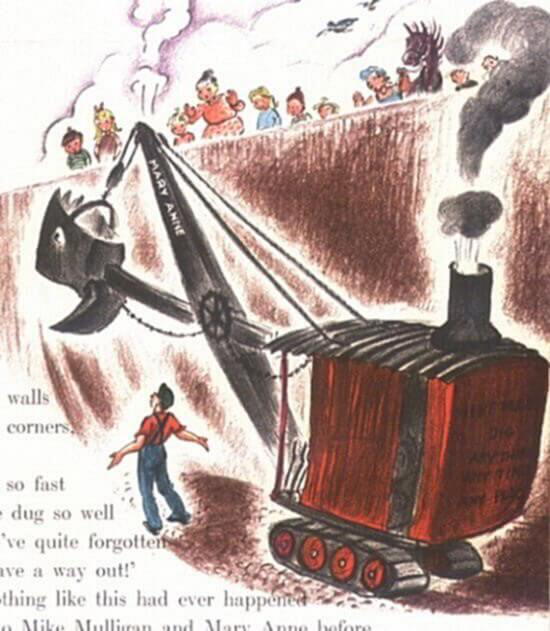

Nevertheless, I keep the end of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel in mind as a cautionary tale. With their enormous audience, Mike and Mary Anne DO accomplish what nobody thought they could: they dig the Popperville town hall basement in just one day. But they’re digging so well and so fast that they forget one crucial thing: they forget to leave a way out for themselves.

Virginia Lee Burton creates a charming ending out of Mike Mulligan’s critical error; Mike and Mary Anne stay in the basement. Mary Anne is converted into the furnace for the new town hall, and Mike serves as janitor. They live out their days in the town hall basement, surrounded by the grateful citizens of Popperville. It’s a happy ending.

After all, this is a children’s book.

But I take away a darker meaning; the ending of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel reminds me that it’s possible to become so engrossed in our work, so caught up in our audience’s validation, that we forget to leave a way out. I love to write, I want to share my writing, and I don’t think that it’s wrong to live in the tension between doing something for yourself and also desiring an audience. But neither of those things is my whole life. Mike Mulligan and Mary Anne taught me that it’s important to always leave a way out, an exit up into the fresh air of the rest of our lives. I don’t want to be trapped in a basement of my own design, no matter how well or how quickly I dug it.